Finding Your Roots

Family Recipes

Season 11 Episode 5 | 52m 10sVideo has Closed Captions

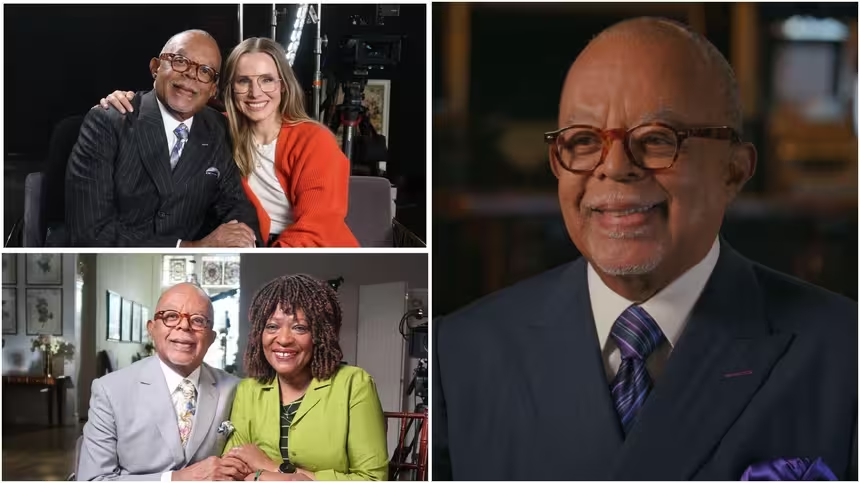

Henry Louis Gates, Jr. explores the ancestry of notable chefs José Andrés & Sean Sherman.

Henry Louis Gates, Jr. explores the family trees of celebrity chefs José Andrés & Sean Sherman—two men who have combined culinary skills with profound humanitarian goals. Traveling from small-town Spain to Native American lands in the Dakotas, Gates explores where these qualities came from, revealing that the ancestors of José & Sean have hidden connections to key moments in history—and to food.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Corporate support for Season 11 of FINDING YOUR ROOTS WITH HENRY LOUIS GATES, JR. is provided by Gilead Sciences, Inc., Ancestry® and Johnson & Johnson. Major support is provided by...

Finding Your Roots

Family Recipes

Season 11 Episode 5 | 52m 10sVideo has Closed Captions

Henry Louis Gates, Jr. explores the family trees of celebrity chefs José Andrés & Sean Sherman—two men who have combined culinary skills with profound humanitarian goals. Traveling from small-town Spain to Native American lands in the Dakotas, Gates explores where these qualities came from, revealing that the ancestors of José & Sean have hidden connections to key moments in history—and to food.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Finding Your Roots

Finding Your Roots is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Buy Now

Explore More Finding Your Roots

A new season of Finding Your Roots is premiering January 7th! Stream now past episodes and tune in to PBS on Tuesdays at 8/7 for all-new episodes as renowned scholar Dr. Henry Louis Gates, Jr. guides influential guests into their roots, uncovering deep secrets, hidden identities and lost ancestors.Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipGATES: I'm Henry Louis Gates Jr.

Welcome to "Finding Your Roots."

In this episode, we'll meet José Andrés and Sean Sherman, two chefs who are using their kitchens to help create a better world.

ANDRÉS: I think we all have, as humans, we all have pride in giving to others a little bit more than, than where we came from.

SHERMAN: As a chef, I could name hundreds of European recipes off the top of my head in European languages.

And knew nothing about Native American or Lakota recipes and the more I went down that path, the more doors opened up and the more clearly, I saw the future.

GATES: To uncover their roots, we've used every tool available.

Genealogists comb through paper trails, stretching back hundreds of years.

ANDRÉS: I, I cannot believe it.

GATES: While DNA experts utilize the latest advances in genetic analysis to reveal secrets that have lain hidden for generations.

SHERMAN: That's amazing.

GATES: And we've compiled it all into a Book of Life.

Let's go, baby.

ANDRÉS: I don't know if I'm ready.

GATES: A record of all of our discoveries.

SHERMAN: That's super, that's super interesting.

GATES: And a window into the hidden past.

ANDRÉS: I mean, wow.

This is almost like realizing that everyone's life is like a movie.

SHERMAN: Oh, man.

That's crazy.

GATES: They went from fighting against the Native populations to marrying into the Lakota.

SHERMAN: Yeah.

GATES: What do you make of that?

SHERMAN: I think it's amazing.

GATES: Yeah.

SHERMAN: I love that history.

ANDRÉS: All these people that we've been going through, they all have a very big piece of, of who I am.

GATES: José and Sean found fame by cooking the dishes of their ancestors.

In this episode, they're going to discover that they share much more in common with those ancestors than recipes, as they learn the stories and the secrets of the people who laid the groundwork for their success.

(theme music playing).

♪ ♪ (book closes).

♪ ♪ (kitchen sounds).

José Andrés is a celebrity chef like no other.

ANDRÉS: They're gonna be so tasty.

GATES: He's won four Michelin stars.

ANDRÉS: Oh.

GATES: Opened dozens of successful restaurants, and is also an heroic humanitarian.

Indeed, as the founder of World Central Kitchen, a nonprofit focused on disaster relief, José has helped bring food to millions of people.

Many trapped in the most dire straits imaginable.

But while his influence spans the globe, José's own story begins in a most humble place, a kitchen in Catalonia, Spain, where his mother, a nurse, inspired him with her creativity.

ANDRÉS: My mom, she will do magic at the end of the month before the next paycheck will come, she will go into the fridge.

GATES: Mm-Hmm.

ANDRÉS: And with the half egg that was halfway dry and a piece of ham or, uh, little piece of chicken left from the roast chicken on the two weekends before she will make croquetas, with bechamel, or she put everything in with the breadcrumbs that were also left over.

And those croquetas will be deep fried.

Oh my God.

That was the best dish that I could ever eat, but this was not a dish out of plenty.

This was a dish out of nothing.

GATES: Yeah.

ANDRÉS: Uh, until the next paycheck will come, and then they will buy again the big chicken and the biggest steak or the fish.

But I never remember those dishes.

I always remember the ones at the end of the month.

GATES: José inherited his mother's tastes and her talents, but for a time he couldn't figure out how to employ them.

The solution came in a very unlikely way.

When José was 18, he joined the Spanish Navy and was given a job cooking on the Juan Sebastián de Elcano, a traditional schooner that was used to train new sailors.

ANDRÉS: That changed my life in more ways, I can't even imagine... GATES: Huh.

ANDRÉS: Because that was a boat that showed me that the winds can come from north or south.

GATES: Mm-Hmm.

ANDRÉS: The currents can come from east or west.

If you have 300 people working together against all odds, you can get... GATES: You could still go, you could move forward.

ANDRÉS: To the place you want.

GATES: Ah, that's great, that's beautiful.

ANDRÉS: And this, for me, was very important, was, uh, a great form of university, was a gift that came in the form of being in an adventure very early in my career.

GATES: Yeah.

ANDRÉS: That I learned about places I never imagined, like Abidjan and Yamoussoukro and, and meeting people and spending time with people I never had the, the opportunity to be with.

GATES: Yeah.

ANDRÉS: Uh, 'cause you grew up with your tribe, and it's fascinating when you meet other tribes.

GATES: Yeah.

José would never lose the perspective that he gained on that ship.

Following his service, he embarked on a mission to reinterpret Spanish cuisine and share it with the world, starting with a series of award-winning restaurants in the United States.

His global perspective ultimately informed his humanitarian work too, as the idea for World Central Kitchen came to him in 2010, when he traveled to Haiti in the wake of a devastating earthquake, volunteered to cook in refugee camps, and learned a profound lesson.

ANDRÉS: That was the moment that I realized that cooks like me, that we feed the few in very unique ways we can feed the many.

GATES: Mm-Hmm.

ANDRÉS: And also gave me a sense of the dignity that food gives to people.

GATES: Mm-Hmm.

ANDRÉS: I'm cooking already in these two, three camps, and as I'm making this amazing bean dish with food I bought locally because the beans were in season, Haiti has amazing beans.

GATES: Hmm.

ANDRÉS: Um, I was making them in the way this Spanish boy learned how to make it in Spain.

The women were singing and when they were helping me, but then when the dish is finished, they come with the translator and they come and, say, "Hey, José, we, we love that you've been cooking with us, but especially these beans, we don't eat them this way."

What?

At That moment, it's like, okay, how do you want them?

Um, you want them as smash?

GATES: Mm-Hmm.

ANDRÉS: It took us two more hours, it's not like we had blenders, it's not like we had electricity.

We found different ways to smash them like they traditionally would do, but we had to feed 500 people at the end the beans were like, they want it.

People don't want our pity, people want our respect.

GATES: Mm-Hmm.

ANDRÉS: And always people tell me, why do you cook local food in the middle of an emergency?

Because actually, it's the easiest, actually, is what gives people dignity and is what gives people hope.

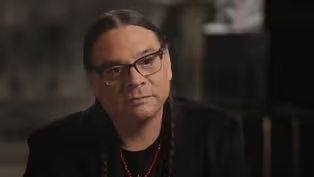

GATES: My second guest is Sean Sherman, the first Native American chef to win the coveted Julia Child Award.

Sean was born on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota, the tribal headquarters of the Oglala Lakota Nation.

Much like José Andrés, Sean also learned to cook in his childhood home.

But Sean didn't grow up preparing the dishes of his ancestors, far from it.

SHERMAN: Like a lot of kids in the '80s we were latchkey, you know, my mom was going to school, working, uh, three jobs and I was the oldest between my sister and myself, so I was doing a lot of cooking.

GATES: Mm-Hmm.

SHERMAN: And I remember just like lots of hamburger helper and, uh, you know, learning how to make some very simple meals, you know, learning how to make sloppy Joe's with just ketchup and mustard, 'cause that's all that was in the fridge, you know?

So, um, figuring out things, you know, and, you know, reading the back of, uh, taco seasoning packs and mimicking that because we didn't have any taco seasoning packs to make the spices taste like that, you know?

GATES: Oh, that's, that's amazing.

SHERMAN: So experimenting and learning how to, to utilize whatever was available to me, which was very little, but utilizing it to the best I could.

GATES: Sean would soon move past his basic recipes.

He got his first job in a restaurant when he was only 13 years old, and took to it immediately.

By the time he was 27, he was an executive chef in Minneapolis and heading towards the very top of the city's restaurant scene.

But then with his path seemingly set out before him, Sean had an epiphany that changed everything.

SHERMAN: I realized the absence of my own heritage in the culinary world.

I realized that, um, as a chef, I could name hundreds of European recipes off the top of my head in European languages, and knew nothing about Native American or Lakota recipes.

I could name maybe five Lakota recipes that I feel like weren't influenced by outside cultures.

So it kind of shot me on a path to understand.

And the more I went down that path, the more doors opened up and the more clearly, I saw the future.

GATES: Sean's future would include an ever-expanding array of institutions designed to revitalize and promote indigenous cuisine.

From food trucks to a high-end restaurant, to educational and training programs aimed at Native communities.

Along the way, Sean's won a slew of honors, both for his recipes and for his social vision.

But to hear him tell it, he's simply trying to honor his roots.

SHERMAN: I feel like I've always kind of gone by a guiding quote, um, be the, "Be the answer to your ancestors' prayers."

GATES: Mm.

SHERMAN: And growing up on, um, a tribal community like Pine Ridge, that's been basically one of the poorest areas in the United States since its inception, seeing so much lack of food access, so much health issues, and so much just trauma issues in general, that this work to me is really important, you know?

So I feel like there is a calling somewhere in there, and I can only hope that some of my ancestry helped gift me some of the skills that I'm utilizing today.

GATES: "Be the answer to your ancestors' prayers."

I like that.

SHERMAN: Thanks.

GATES: Sean and José share a noble goal.

They're using their talents and their resources to help others, trying to alleviate hunger and hardship throughout the world.

Now they're going to be able to see how much hardship their own ancestors endured.

For José, this meant going back four generations to his paternal great-great-grandmother, a woman named Oracia Cecilia Ladislá.

Oracia was born sometime around 1845, likely near Almeria, a city in southern Spain.

As we comb through the record she left behind, we noticed something striking.

In 1870, Oracia gave birth to a daughter, and on her daughter's baptismal record, Oracia is described as being an exposita.

ANDRÉS: Exposita is what?

GATES: It means she was abandoned.

She was abandoned by her parents as an infant.

ANDRÉS: Wow.

GATES: What's it like to learn that?

ANDRÉS: That's fascinating.

GATES: Think about this... Oracia carried the status of an, an abandoned child, or a foundling, as we would say in English her entire life.

Even at her daughter's baptism, they're still calling her a foundling, an exposita.

ANDRÉS: Well, this only tells you that, uh, uh, many, the so-called traditions of what we expect about humans, about what is the right or wrong behavior, um, very often it doesn't work in real life.

GATES: Yeah.

ANDRÉS: Uh, that to make a woman, uh, be ashamed if something happen, um, is probably never the right thing to do back then and not today.

GATES: Mm-Hmm.

ANDRÉS: Life, life things happen.

GATES: Mm-Hmm.

ANDRÉS: And I think very often, more than not to woman... GATES: Mm-Hmm.

ANDRÉS: Uh, the, the traditions, the social traditions, and what is right and what is wrong.

GATES: Mm-Hmm.

ANDRÉS: Always has played against women.

GATES: Always, yeah, because men were making the rules.

(laughter).

We weren't able to identify Oracia's biological parents.

However, we did manage to learn a surprising amount of detail about her life.

Starting in the archives of what's known as the Almeria Foundling Home.

Here, we uncovered a record that describes exactly how Oracia was abandoned.

ANDRÉS: "She was put through the main torno at 8:15 PM on the 27th of June 1845, wrapped in two old bags."

Wow.

GATES: "Wrapped in two old bags."

Have you ever heard of a torno?

ANDRÉS: Yeah, the torno, um, in many of the convents, uh, were las monjas de clausura, the, the nuns.

GATES: Mm-Hmm.

ANDRÉS: Don't have any connection with outside world.

GATES: Mm-Hmm.

ANDRÉS: But the torno will be the, the way to, even to this day, you can go to some monasteries in Spain and still some of these monasteries, those convents.

GATES: Right.

ANDRÉS: And where the nuns will pay the bills, uh, making cookies and selling traditional cookies, or honey all the things.

And the way you will... GATES: Communicate... ANDRÉS: Get those cookies will be through that torno and the way you will pay.

And that's, that's the way it still to this day.

GATES: And it's also where if you wanted to abandon your child, put up your child, give it to the nuns, you put it on the torno.

ANDRÉS: Wow, that's, that's fascinating.

GATES: Most abandoned children face dismal prospects.

Indeed, many did not live beyond infancy.

But Oracia beat the odds.

Sometime before her fourth birthday, she was taken in by a couple named Maria and Sebastián Vicente.

They not only raised her, but they also put aside money so that she would have a kind of trust fund when she became an adult.

An extraordinary arrangement that raised the fascinating question, could the couple have been acting on behalf of Oracia's biological family?

ANDRÉS: Oh my God.

GATES: Yes.

Why would they adopt this child and give her all this money?

We think that it's possible that they knew the birth parents and they were making things right.

We don't know.

But it seems plausible.

ANDRÉS: That even they could be the parents themselves.

GATES: Yeah, they could be, they could be.

ANDRÉS: But we'll never know.

GATES: Three years later, but we'll never know.

ANDRÉS: Wow.

GATES: According to the scholar, we consulted the documents would make sure not to reveal the details.

So the truth is lost to history.

ANDRÉS: That's good news, even this happened long time ago.

Uh, obviously this only shows you that life, moves on.

GATES: Mm-Hmm.

ANDRÉS: Western churches said that success was going from failure to failure without losing enthusiasm.

I, I believe in the hard times, you keep going.

But I'm happy that, obviously I'm thrilled, you know, obviously I made it here, so something had to go right at one moment.

GATES: That's right, or you wouldn't be here, baby.

ANDRÉS: Oh my God.

GATES: Regardless of whether or not they were or Oracia's relatives, Maria and Sebastián clearly felt a deep love for her.

And Oracia seems to have flourished thanks to their efforts.

In July of 1864, she even started a family of her own marrying José's great-great-grandfather, a man named Miguel de la Casa Rova.

ANDRÉS: Wow.

GATES: What's it like to think of all Oracia had been through to get to that day?

ANDRÉS: Fascinating, and she married young 19.

GATES: And married a younger man.

ANDRÉS: 17, unbelievable.

GATES: Yeah, and guess what?

After your great-great-grandparents married, they received that money.

They received Oracia's trust.

They started their family and they began working as bakers.

ANDRÉS: No.

GATES: They were bakers, baby.

ANDRÉS: Ah, amazing.

GATES: You came by it naturally.

ANDRÉS: I was telling my wife the other day, like, one of the things I'm gonna do when I grow older is we're gonna move to a town, could be in Haiti, could be in Spain, can be in Dominican Republic, but the town, we feel like our contribution can help the town, and one of the things I'll do a bakery that will do the traditional bread in the place we are, uh, whatever.

So it's kind of fascinating.

GATES: It is, you descend from bakers.

ANDRÉS: The bread that keeps on giving.

GATES: There is a final beat to this story.

In 1893, Oracia's daughter, José's great-grandmother, Leocadia became a teacher, a sign that she was well-educated, and now a member of the middle class.

What do you think that was like for Oracia?

She gave her daughter what she never had.

ANDRÉS: You know, um, my, my father, my mother, they were nurses.

Um, uh, my, my brothers, none of us, uh, went to university.

Uh, but we done well in different businesses.

Uh, for me, I'm not gonna lie to you, it is been a huge, huge, um, pride to know that my three daughters, they, they're going through university.

GATES: Yeah.

ANDRÉS: So I think we all have, as humans, we all have pride in, in, in giving to others a little bit more than, than where we came from.

GATES: Right.

ANDRÉS: And I think this is the best story of humanity, that we all always work hard in a way, not only for us.

GATES: Mm-Hmm.

ANDRÉS: But in a way to try to push the people that come after us, forward.

GATES: Absolutely, yeah.

ANDRÉS: And here we see it many times.

We see it with, with, uh, the money that was left... GATES: Yes.

ANDRÉS: For, for future.

And that is the gift that keeps on giving, everybody tries to push, uh, everybody, uh, every younger generation forward.

GATES: Much like José, Sean Sherman was about to encounter an ancestor who created a family in the face of extraordinary odds.

The story begins where Sean himself was born, the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota.

Sean's great-grandfather, a man named John Conroy, moved to this reservation sometime in the late 1870s, along with his mother, a Lakota woman named Yulala.

But John's father did not accompany them.

And in the reservations archives, we saw the likely reason why.

John's father, Sean's great-great-grandfather was named Thomas Conroy.

And Thomas was a White man born in Ireland.

Did you know that?

SHERMAN: I did, yes.

GATES: What is it like to see that written down in an official document?

SHERMAN: Um, you know, like I, I've always known about that line of things about where the Conroy line comes from.

Um, my mother had a lot of, um, Irish pride growing up, which is why myself and my sister became Sean and Kelly.

GATES: I was thinking that, yeah.

(laughter).

SHERMAN: And so I understood that that tie, um, and, you know, and I actually, I love Ireland.

I've been there a couple of times, and I love that culture.

So I'm, I'm happy to have that culture in me.

GATES: My great-great-grandfather was Irish... SHERMAN: There you go.

GATES: There you go.

Have you heard much about your great-great grandparents' relationship?

SHERMAN: No, I don't really know too much about that part of it, you know, except for I knew that she had moved away from that.

And I can only imagine that it probably wasn't a very pleasant relationship, but I don't know much about it.

GATES: According to this record, Thomas and Yulala married sometime around 1855 under what were described as Indian customs.

Their son, John was born roughly five years later in Fort Laramie, Wyoming, where Thomas was working as a blacksmith likely for the United States Army.

SHERMAN: That's super, that's super interesting.

GATES: Blacksmiths like Thomas were crucial in providing materials necessary to supporting the soldiers and the civilians who lived in the area.

SHERMAN: Mm-Hmm.

GATES: So how do you imagine Thomas and Yulala met?

SHERMAN: Oh, I would imagine that there was a lot of intermarrying happening during that time period, 'cause I do know that there was a lot of, um, um, Native community kind of moving around the forts, you know, and also there was a lot of things that weren't pleasant.

There was a lot of people that were being stolen and being forced to be wives too.

GATES: Right.

Well, we're not certain, but according to the scholars, their relationship was not unusual.

SHERMAN: Yeah.

GATES: For the reasons that you can imagine.

SHERMAN: Yeah.

GATES: It would've been fairly common for men stationed in military forts to have some sort of marriage or liaison with... SHERMAN: Yep.

GATES: ...an Indigenous woman, though these relationships were often short-lived.

SHERMAN: Yeah, absolutely.

GATES: We don't know how long Thomas and Yulala were together, but their relationship overlapped with a terrible period in American history.

As the United States government pursued a brutal policy of Western expansion, seizing Native lands and redistributing them as it saw fit, all the while violently displacing and dispersing Native peoples.

Ironically, Sean's great-great-grandfather, Thomas was not only a witness to this period, he seems to have tried to profit from it.

In November of 1867, when his son, John, was roughly eight years old, Thomas was one of 157 men from Fort Laramie who signed a petition asking the United States government to provide land for their very own Indian reservation.

Did you ever hear about this?

SHERMAN: No.

GATES: Well, Thomas and the other petitioners describe themselves as "heads or members of Indian families," quote-unquote.

So it seems as if Thomas may have been trying to obtain land... SHERMAN: Mm-Hmm.

GATES: From the federal government based on his relationship, of course, to Yulala.

SHERMAN: Yeah.

GATES: And John, did you ever imagine you had a white Irish ancestor, tried to start an "Indian reservation," quote-unquote, for mixed ancestry Native families?

SHERMAN: I mean, there, yeah.

I mean, families are complicated as you would know, but, you know, it's, that's a lot, that's a lot.

GATES: Sean, this is the only record we found of Thomas referencing that he had children with a Native American woman.

How does it feel to know that?

SHERMAN: Um, yeah, I mean, it feels, uh, I don't know much about, um, this person really in my family.

I mean, I, I know the name, I knew a little bit about where he came from and I understood kind of the circumstance, but I don't know that much about him, but it seems, uh, you know, again, not, not the best circumstances.

Um, you know, and it feels like he's using this situation for his benefit as much as he can.

GATES: Thomas's petition was denied and there's no evidence he ever received any land from the federal government.

But in the 1880 census for Laramie County, we discovered that his relationship with Yulala was even more complicated than it first appeared.

SHERMAN: Thomas Conroy, White, 50, married, blacksmith, place of birth, Ireland, Alice, White, 47, keeping house, Maggie White, 15, daughter, Charles White, 17, son, John White, 12, son.

GATES: Any idea of what you just read?

SHERMAN: Uh, I'm not sure the date's confusing for me.

GATES: Well, Thomas is now married to a White woman named Alice Gilchrist.

SHERMAN: Okay.

GATES: And he has a new family, a White family, including a White son named John, quote-unquote.

SHERMAN: Okay.

GATES: Records show that Thomas and Alice were first married in 1854, Sean.

SHERMAN: Okay.

GATES: About a year before Thomas married your great-great-grandmother Yulala.

SHERMAN: Right.

But unofficially, 'cause if they're saying it was... GATES: "Indian customs."

SHERMAN: Indian customs.

GATES: Right, so they seemed to have been separated for a time and then reunited around 1861.

SHERMAN: Okay.

GATES: Did you have any idea that he had these two families?

SHERMAN: Uh, I knew that he went on to have a different family, so I didn't, but I don't know anything about that side of it.

GATES: Well, they were simultaneous.

SHERMAN: Oh yeah, gotcha.

GATES: Yeah.

SHERMAN: Okay.

(laughter).

GATES: Yeah.

SHERMAN: I see now, I see now.

GATES: Yeah.

The family story is that Thomas and Yulala separated after Yulala discovered Thomas had reunited with his former wife, Alice.

SHERMAN: Oh, yes.

GATES: 'Cause he marries Alice before he, he meets Yulala.

SHERMAN: Right, and that makes sense, you know.

GATES: Now remember though, Thomas signed a petition to create that reservation for mixed ancestry Native families.

SHERMAN: Yeah.

GATES: In 1867, about six years after he got back together with his White wife, Alice.

SHERMAN: Sure.

GATES: So what's going on here, man, this is like, he was doing a dance back and forth between wives and identities.

SHERMAN: Absolutely, but they saw the opportunities that were out there, I mean, they were handing out Native land like candy back then too, you know, so they were doing everything they could to secure some wealth.

GATES: Do you think Thomas ever saw your great-grandfather John again?

SHERMAN: I don't know that.

GATES: Mm.

SHERMAN: Yeah, I don't know that, yeah.

GATES: According to Sean's family, after Thomas and Yulala separated, their mixed-race son, John lived for a time with his White father.

John's obituary published in 1950, supports this story and also details how Yulala eventually took her son back.

Have you ever seen that?

SHERMAN: Uh, no, I don't believe so.

GATES: Well, according to this record, sometime after his parents separated, John and his mother traveled through the Sioux territory to be raised with her people.

SHERMAN: Mm-Hmm.

GATES: So how do you think John felt at the time?

Not only were his parents separated, but he was now going to start a new life without his father.

SHERMAN: Yeah, I mean, I, I can imagine that it was a massive transition, but I can imagine his mother just really wanted him to experience being Lakota.

GATES: Mm-Hmm.

SHERMAN: You know, and to really, um, share the importance of this, especially 'cause she had to have known too what was going on at this time period, being an adult and seeing a lot of the aggressiveness happening against Lakota and Cheyenne 'cause it's during this time period, there's a lot of bad things starting to happen out there in the West, you know?

GATES: Yeah.

Can you imagine what your life would've been like if John had been raised by Thomas' Irish father?

SHERMAN: Yeah, absolutely completely different, obviously, you know, and I'm really, you know, uh, I've always loved that part of the family history that they did go back to Lakota.

GATES: Mm-Hmm.

SHERMAN: And that they did have that experience, even though they are forced, um, eventually rather quickly back into a reservation system on Pine Ridge.

And, uh, I think that you know, we should be having a deeper understanding of all of this, of all of this diversity, all of this trauma, all of this violence, all of this dark history and that's how we have to move forward.

We have to take that understanding, we have to feel that pain to be able to grow.

GATES: We'd already seen how José Andrés', great-great-grandmother Oracia, overcame a childhood of immense adversity.

Now turning to another line of José's father's family tree, we encountered an ancestor who faced a very different ordeal.

José's third great-grandfather, José Andrés Tortosa was born in Spain in 1802 and grew up during a time of intense political turmoil.

Throughout his youth, liberals seeking to create a democracy struggled against the Spanish crown.

After a brief success in the early 1820s, they were systematically suppressed.

And in 1824 an armed uprising broke out just miles from José's hometown as royal troops battled with rebel forces around the walled city of Almeria.

José, your third great-grandfather was just 22 years old at the time.

Now, I want you to guess which side was he on.

ANDRÉS: This is fascinating.

I would believe he will be in the, at the time, in the more liberal side, probably.

GATES: Mm-Hmm.

ANDRÉS: I'm only guessing.

GATES: Okay, that's your vote?

ANDRÉS: That's my vote.

GATES: Let's see what happened next, please turn the page.

ANDRÉS: Uh-oh.

GATES: This is from the municipal archives of Almeria 1841.

It's an entry from a list of people who took part in the uprising of 1824.

Would you please read that translated section?

ANDRÉS: Known as José Andrés Tortosa, resident of the Town of Íllar, for having acted with weapons in hand, along with the expeditionaries.

GATES: Bingo, your ancestor, your third great-grandfather, was a rebel.

ANDRÉS: Unbelievable that you can find this.

Oh my God.

GATES: What do you make of this?

Think about this, I'm sure that it would've been reasonable for you to think about yourself as a revolutionary, as an agent of social change, right?

And thinking you're the first one in your family, but you weren't.

ANDRÉS: But it, it is fascinating because I, I, I, I see myself more, uh, uh, as a centurist, right, I'm, I'm a I'm a business guy in a way.

I'm a cook, now I run restaurants.

GATES: Mm-Hmm.

ANDRÉS: And when you run restaurants or you're a cook, seems you are more on the leaning right, or, uh, but in other ways, I'm like, I believe I wanna do well, but I don't wanna do well at the expense of others doing badly.

GATES: Right.

ANDRÉS: So call me more liberal, more.

And at the end, I always believe that it is the perfect medium somewhere.

Um, um, but what is very important is that, um, used to be there fighting for the right, for people to, to vote.

GATES: Right.

ANDRÉS: Um, man, uh, fascinating that this seems, uh, that you had to do a revolution to achieve that, right?

GATES: Yeah, that's right.

ANDRÉS: It seems.

But right now we are fighting for the same thing in America and in other places of the world.

GATES: José's ancestor was lucky that his idealism didn't cost him his life.

When the uprising failed, at least 20 of his fellow rebels were executed.

And many more faced imprisonment or exile.

Where still, Almeria was just one of dozens of insurgencies that consumed Spain over the next decade.

And none succeeded.

But José's ancestor not only survived these painful times, he also managed to hold onto his principles.

And in 1841, roughly 17 years after he took to the streets, the liberals regained power and recognized their old ally.

ANDRÉS: The commission named by the city council to report unclassified individuals it deems are worthy of the Civic Award granted by the Regent of the Royal, by decree of the 25th of August past.

Following the incidents that occur in this capital in the year 1824, in order to restore the national freedom, the subjects are Don José Andrés Tortosa.

GATES: José.

ANDRÉS: Wow.

GATES: In 1842, the Spanish region awarded your third great-grandfather the Civic Cross for his participation in the uprising.

ANDRÉS: How crazy.

Wow.

GATES: This award wasn't the only recognition that José's ancestor would receive for his service, when he passed away in 1884, at the age of 82, his obituary reveals that he was still remembered and celebrated by his fellow citizens and that he'd never abandoned their shared dreams.

ANDRÉS: He goes to his grave with the satisfaction of having caused no harm to anyone in his long life.

GATES: Mm-Hmm.

ANDRÉS: Although modestly, he was a member of the old progressive party and never faltered in the course of its development.

May he find the repose which his merits and humanitarian sentiments have earned him.

GATES: Your third great-grandfather continued to support progressive politics for the rest of his life.

He participated in almost, José, every reformist political and social movement in Spain from the 1840s and to his death.

What's it like to learn about this long-lost ancestor?

ANDRÉS: I mean, it feels good, is when I became American on the day we were swearing in my wife and I, they told us that to be part of America, uh, was not only being part of on election day but was to be part of democracy every single day with contributions, small or bigger, with, uh, raising your voice and speaking up.

And I guess, um, very much, I guess he embraces also these ideals of, of America.

GATES: Yeah.

ANDRÉS: To be part of America is just contributing to America be a little bit better.

Uh, and I guess he tried to do the same for, for Spain.

GATES: We'd already seen how Sean Sherman's maternal ancestors met in Fort Laramie, Wyoming, as White Americans were violently encroaching on Native lands in the West.

Now turning to Sean's father's roots, we found ourselves revisiting that painful era.

The story begins in 1879 when Sean's great-great-grandmother, a young woman named Lizzie Glode was taken from her family home in South Dakota and sent east to Pennsylvania to attend what was known as the Carlisle Indian Industrial School.

Carlisle was the first of many boarding schools designed to assimilate Native children into White society.

And Sean knows a great deal about its dark history.

But we were able to personalize that history, starting with a letter written by the school's founder, describing how his first pupils had been selected.

SHERMAN: Through the efforts of the acting agent, agency employees, the missionaries, and chiefs, five female and 10 male children were brought in.

The following is a list of the children brought to Carlisle from Rosebud and Pine Ridge Agency's English name Daisy Glode, age 15, banned Oglala.

GATES: Have you ever seen that document?

SHERMAN: I have not, no.

GATES: Sean, this is the moment that your great-great-grandmother, Lizzie recorded there as Daisy was selected to go to the Carlisle School, and she was just 15 years old.

SHERMAN: Okay.

GATES: How does it feel seeing that?

SHERMAN: I mean, I know of a lot of the atrocities that happened there 'cause I've visited there and I've seen the graveyard of all of the young Native, um, children that lie there and had actually that graveyard is a third of the size that it used to be, they moved all the graves because it was taking up too much space on their campus, you know?

Um, but, uh, there's just a lot of pain that happens, um, in Carlisle, and that that whole methodology of assimilation, of course, spreads like wildfire across the U.S. and Canada.

GATES: Carlisle's founder was an army veteran named Richard Henry Pratt.

Pratt had fought against Native Nations on the Great Plains, and he founded his school with the financial support of the United States government, believing that Indigenous peoples could only be integrated into White society if they gave up their traditional cultures.

With this goal in mind, Pratt traveled across the West trying to persuade tribal leaders to send him their own children without any regard to all that would be lost in the process.

SHERMAN: The fathers of these children are chiefs or leading men in their tribes and while the training and development of their children into manly self-supporting men and women goes forward, their parents, relatives, and friends will be restrained by the fact and incited to seek for themselves a better state of civilization.

They have great affection for their children, thousands gathered at each agency to see them off and more affecting tears, grief, and mourning could not be imagined.

Chiefs whose names are known all over the country, exhibit all the emotions of the kindest natures.

GATES: Uh, so can you imagine?

SHERMAN: So much pain, you know, and, you know, I've seen pictures of, you know, the train cars filled with Native, young, Native children.

Um, and I can only imagine the grief of the mothers and the grandmothers who have been raising everybody, you know?

And I've always understood that this has been a part of the family, uh, that this has lived with us, you know, and knowing what they're going to doesn't help, you know?

GATES: I mean, you could tell that even though the chiefs are sensibly acquiesced to send some of their children to the school, this was a devastating separation.

SHERMAN: Yeah, I mean, they were left with no choice because either they send the children or they get no food, supplies or anything that else is, whatever's been promised to them, you know, 'cause they're basically prisoners of war at this point.

GATES: Right.

To separate its students from their Native culture, The Carlisle School imposed strict regulations on dress, grooming, and speech.

So when Sean's great-great-grandmother, Lizzie arrived, she would've been forced to cut her hair, don a uniform, and abandon her native language or risk harsh punishments.

What's more, Lizzie and her fellow students also faced abuse, malnutrition, and disease.

How do you think she managed to persevere?

SHERMAN: I don't think you have a choice, I feel like you find your strength, I feel like you go through it no matter what happens, you know?

And it's, uh, it's just, that's, that's part of it, you know?

And, you know, humor probably comes through a little bit because we, as a lot of people of color, we share a lot of humor because we kind of have to.

GATES: Yeah.

SHERMAN: We have to look at the world through a different lens sometimes when everything's stacked against us, you know?

GATES: To laugh to keep from crying.

SHERMAN: You kind of have to.

GATES: Yeah.

Carlisle's brutal policies caused students so much stress that many tried to run away simply to survive.

Tragically others died without ever seeing their families again.

But somehow Lizzie endured.

Indeed, we found several photographs of her in Carlisle's archives.

Including one taken near the very end of her stay at the school.

What's it like to think about that?

SHERMAN: You know, I know part of what Carlisle, who was trying, the only proof that they were really showcasing was that were photos, you know?

So they would take a photo of the students upon arrival in their traditional wear, which they usually, they're travel worn.

And, um, you know, they had been living in train cars for days, weeks, or however long it takes these journeys to happen.

Um, and then they trans, they cut their hair, they dressed them up and in civilized clothes, you know, and, um, and they were trying, they were trying to showcase this transformation through this trick of photography.

GATES: Mm-Hmm.

SHERMAN: Even though this transformation wasn't happening internally.

GATES: Mm-Hmm.

SHERMAN: You know, and the trauma, the, the violence, the sexual abuse, the mental abuse, the physical abuse, all these things are now living in these children, despite that this costume that they're now wearing.

GATES: Any sign of that?

SHERMAN: I, you can see it in her eyes, you know, you can see that this is, uh, these photos are not by choice.

GATES: This story does have a grace note.

Four years after entering the Carlisle School, Lizzie was transferred to another Indian boarding school in Genoa, Nebraska.

And there she found an occupation that would prove especially meaningful to Sean.

Your great-great-grandmother Lizzie worked as a cook.

SHERMAN: Nice, we've got a good connection there.

GATES: How about that?

SHERMAN: That's right.

GATES: Feeding the students for the school.

Did you have any idea that anywhere in your family tree you had an ancestor who was a professional cook?

SHERMAN: No, I did not, I did not.

(laughter).

No, that's great.

GATES: How do you think she felt about cooking?

SHERMAN: I mean, I personally love cooking.

For me, it's an escape, it's something that I love to do.

It's something that feeds people, you get instant gratification off of making something good that people enjoy.

And I can only imagine that it was a safe place to be because there's food around you also.

GATES: Oh, yeah.

SHERMAN: And it's warm.

It's better than working outside, which what I found out rather quickly, growing up in South Dakota, I'd rather be inside by an oven than outside shoveling snow or delivering newspapers in six feet of snow, you know?

(laughter).

So, um, yeah, I'm sure she found some solace there, 'cause I've, I've found it personally.

GATES: Turning from Lizzie to another branch of Sean's father's family tree.

We found one more story to share.

It starts with a question that Sean brought to us.

Just months before our interview, he'd seen a photograph of his great-great-grandfather, a man named Thomas Shepherd.

The photo strongly suggests that Thomas was Black and Sean was hoping to learn as much as possible about his life.

Records show that Thomas was in fact, an African American.

He was born in Georgia around 1844, 17 years before the start of the Civil War, which means that he almost certainly was born into slavery.

Have you given much thought since you saw that photograph about having an ancestor who was enslaved in the, what became the Confederacy?

SHERMAN: I mean, my assumption was that uh, to be Black in the South during that time period would've been, I would've been the history of things, you know, but that's why I'd be, I was very curious to see if there was any way to learn more about that branch of the family, to learn more about the struggles that they went through.

Um, and to learn, just to learn, you know?

GATES: Well, let's see what we found out.

SHERMAN: Alright, let's do it.

GATES: Would you, you please turn the page?

This is a record from the National Archives in Washington, D.C. it's dated June 7th, 1867, would you please read that transcribed section?

SHERMAN: I, Thomas Shepherd, do hereby acknowledge to have voluntarily enlisted this 7th day of June, 1867, as soldier in the army of the United States of America for the period of five years, sworn and subscribed to at Detroit, Michigan.

Thomas Shepherd, his x mark assigned to the 10th regiment of Calvary U.S. Army.

GATES: There's your great-great-grandfather at 23 years of age, enlisting in the United States Army just two years after the end of the Civil War.

SHERMAN: Interesting.

GATES: Isn't that Incredible?

SHERMAN: Yeah, that's incredible.

GATES: Thomas was assigned to the 10th Calvary Regiment, the army's most famous unit of all Black troops, legendarily known as the Buffalo Soldiers.

He likely saw it as an opportunity, at the time the military offered Black men, including many newly freed slaves, the chance to earn money and be treated with a measure of dignity, even though the army was thoroughly segregated.

But Thomas's service would also send him West, where the Buffalo Soldiers were being used to subdue tribal nations.

SHERMAN: Wow.

GATES: How do you think Thomas felt about all this?

SHERMAN: It's hard to know, you know, it's really, it's really, really hard to know, um, knowing where he came from, what, uh, uh, having an idea, at least where he came from and what he experienced growing up.

GATES: Mm-Hmm.

SHERMAN: And it's hard to know how he was viewing, um, what the job in front of him was.

GATES: Do you think it's reasonable to assume that the African American soldiers shared the views about Native Americans?

That their White, um, compatriots in the Army did?

SHERMAN: I would have to imagine that, um, you know, anybody of color working for the U.S. military would've seen, um, seen through a lot of the hypocrisy that was going on, a lot of the deep racism that was just there.

Um, and it was very present and, you know, prevalent at those time periods.

And I can imagine there was a lot of mixed feelings about what was actually happening.

GATES: Thomas likely had very little time to sort out his feelings.

Just two months after enlisting, he found himself on an expedition to quell Native resistance to railroad construction.

His company was attacked near a fort in present day, Phillips County, Kansas.

And a report written by his captain shows that Thomas was among the wounded.

His company fought against over 400, Cheyenne... SHERMAN: Cheyenne.

GATES: And Kiowa.

SHERMAN: Okay.

GATES: And Lakota at the Battle of Prairie Dog Creek.

SHERMAN: Oh, okay, okay.

I mean, that's crazy, so that's crazy.

GATES: And, and that's a painting of it.

SHERMAN: Oh man, that's crazy.

GATES: And your ancestor was wounded.

SHERMAN: Wow.

GATES: No family stories about that.

SHERMAN: No, no, but I'd love to dig into that, uh, that piece a little bit more.

GATES: Please turn the page.

SHERMAN: Okay then.

GATES: Sean, this is a report from the United States War Department Surgeon General's office from the year 1871.

Would you please read that transcribed section?

SHERMAN: Corporal Thomas Shepherd Troop F 10th Calvary, Beaver Creek, Kansas, August 21st, 1867, arrow wound of the neck.

Oh, wow, that can't be comfortable.

GATES: Can you imagine being shot in the neck with an arrow?

SHERMAN: No, I cannot.

GATES: I gotta ask you, so what's it like to read this on the one end, it's your ancestor being wounded on the other, he's fighting for the United States Army against Native people.

SHERMAN: I know, I mean, the, again, like there's a lot, there's a lot of going, there's a lot going on, there's a lot of feelings there.

And, uh, yeah, I don't, I don't know, like, uh, it's, I mean, and I understand history and I understand how history works, but it's a lot to process, so.

GATES: It's a lot to process.

SHERMAN: Yes, absolutely.

GATES: Fortunately, Thomas survived his wounds.

He would be discharged five years later on June 7th, 1872 in what is now the state of Oklahoma, but was then called "Indian territory."

Thomas's time in the army had a profound effect on the course of his life.

Although he had been born in Georgia, we found him in the 1880 census, starting a family with Sean's great-great-grandmother.

SHERMAN: And this is Dakota Territory, so.

GATES: Yep.

1880, eight years after he was discharged.

SHERMAN: Right.

GATES: He is married with two children.

SHERMAN: Right.

GATES: To a Native American.

SHERMAN: Right.

GATES: The brother did the right thing.

After his service, Thomas stayed out West, married your great-great-grandmother, Alice, a Lakota woman, and started a family.

Records even show that Thomas was eventually considered quote-unquote, "adopted member of the tribe."

SHERMAN: Oh, nice.

GATES: So you gotta admire this guy, he went from fighting against the Native populations to marrying into the Lakota.

SHERMAN: Yeah.

GATES: What do you make of that?

SHERMAN: I think it's amazing, I love that history.

GATES: Yeah, me too.

He goes, I don't want him to get shot in that airway.

(laughter).

SHERMAN: Right.

GATES: Do you think he felt bad about his service as a Buffalo Soldier?

SHERMAN: Oh, there's gotta be a lot of conflicts with that whole situation, yeah, I can only imagine.

So, I mean, I just, there has to be, there has to be.

GATES: Do you think he and Alice ever talked about this?

SHERMAN: I'm sure, I'm sure, he has to.

GATES: Alice said, "What were you thinking?"

(laughter).

The paper trail had now run out for Sean and José.

It was time to show them their full family tree... Unfurl that.

Now filled with people whose names... SHERMAN: Oh wow.

GATES: They'd never heard before.

ANDRÉS: Oh, that's a gift.

GATES: For each was a moment of awe.

ANDRÉS: This is, this is crazy.

GATES: Offering the chance to see how their own lives... SHERMAN: Amazing.

GATES: Were part of a larger family story.

ANDRÉS: All these people that we've been going through, my ancestors, they, they all have a big, very big piece of, of who I am.

SHERMAN: This is beautiful, it opens up so many more doors to learn about myself, my family, and the history of things and also America when it comes down to it, 'cause this is American history.

GATES: That's the end of our journey with Sean Sherman and José Andrés.

Join me next time when we unlock the secrets of the past for new guests on another episode of "Finding Your Roots."

Video has Closed Captions

Preview: S11 Ep5 | 30s | Henry Louis Gates, Jr. explores the ancestry of notable chefs José Andrés & Sean Sherman. (30s)

José Andrés Discovers His Ancestors Were Bakers

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S11 Ep5 | 4m 41s | José discovers his paternal great-great grandmother was abandoned and given to nuns as a baby. (4m 41s)

Sean Sherman Learns About A Tragic Past

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S11 Ep5 | 4m 7s | Sean learns of his ancestor who was sent to the Carlisle Indian Industrial School. (4m 7s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship

- History

Great Migrations: A People on The Move

Great Migrations explores how a series of Black migrations have shaped America.

Support for PBS provided by: